This June marks the 60th anniversary of the Equal Pay Act, which mandated equal pay for equal work and sought to eliminate gender-based disparities in compensation. Signed into law by President John F. Kennedy on June 10, 1963, this historic legislation recognized that women’s work—and their fair and equal treatment in the workplace—is vital to our country’s economic prosperity. This post highlights the significant strides in educational attainment, employment, and pay that have been made since the law was enacted and calls attention to gender gaps that remain in important aspects of employment.

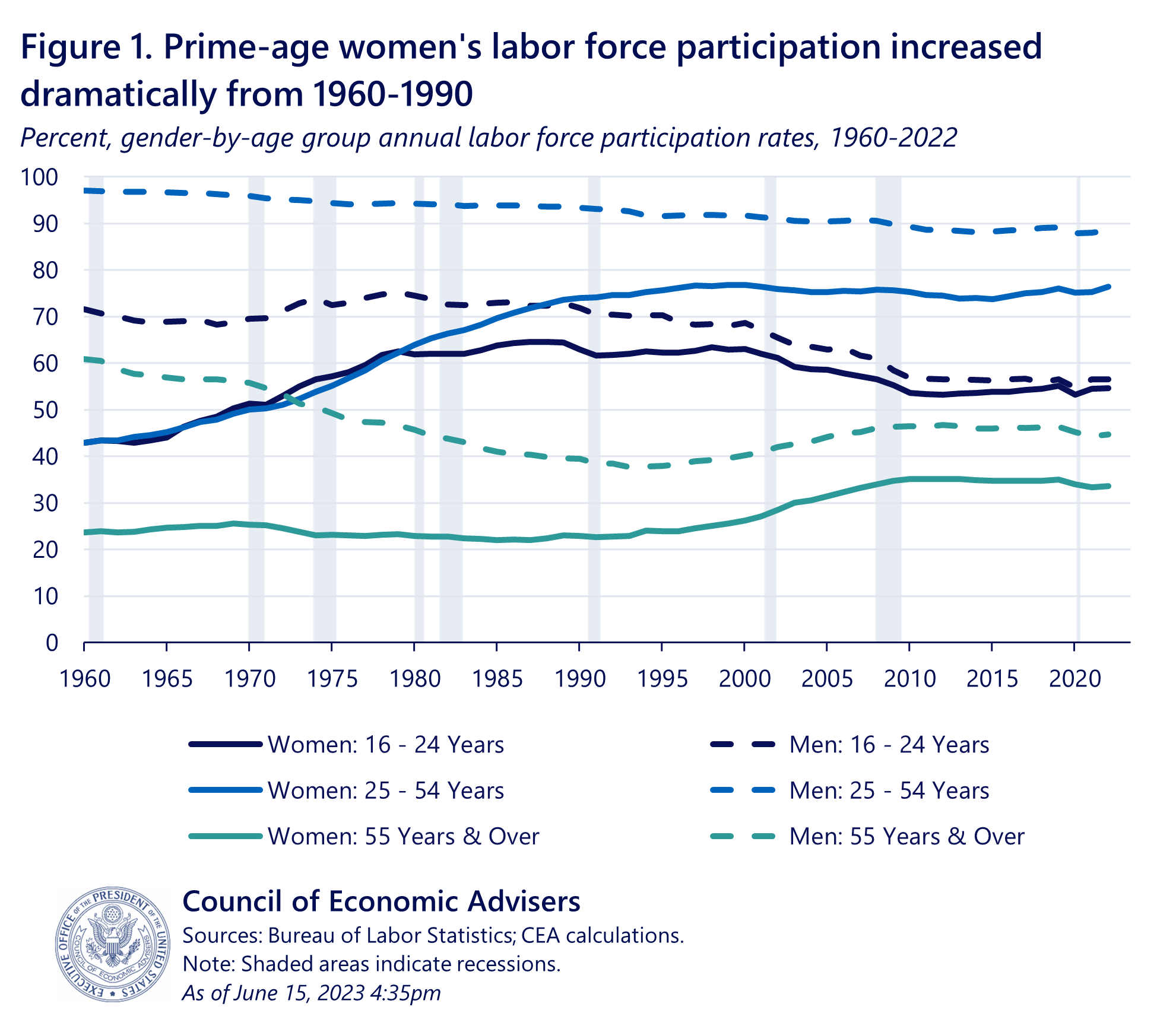

First, the good news: women have made great progress in the workforce since 1963. Labor force participation for prime-age (ages 25 to 54) women—whose employment decisions are less likely to be affected by schooling and retirement—grew throughout the latter half of the 20th century, and the gap between their participation and that of prime-age men shrunk to less than one-third of its previous size (figure 1). In fact, prime-age women’s labor force participation hit a record high in the recent May employment situation report (data series began in 1948).

That said, the progress in prime-age women’s labor force participation seen in earlier decades has slowed in the 1990s, and even experienced periods of decline since the 2000s. With the exception of young people in the labor force, participation gaps between men and women have remained largely the same since the early 2000s.

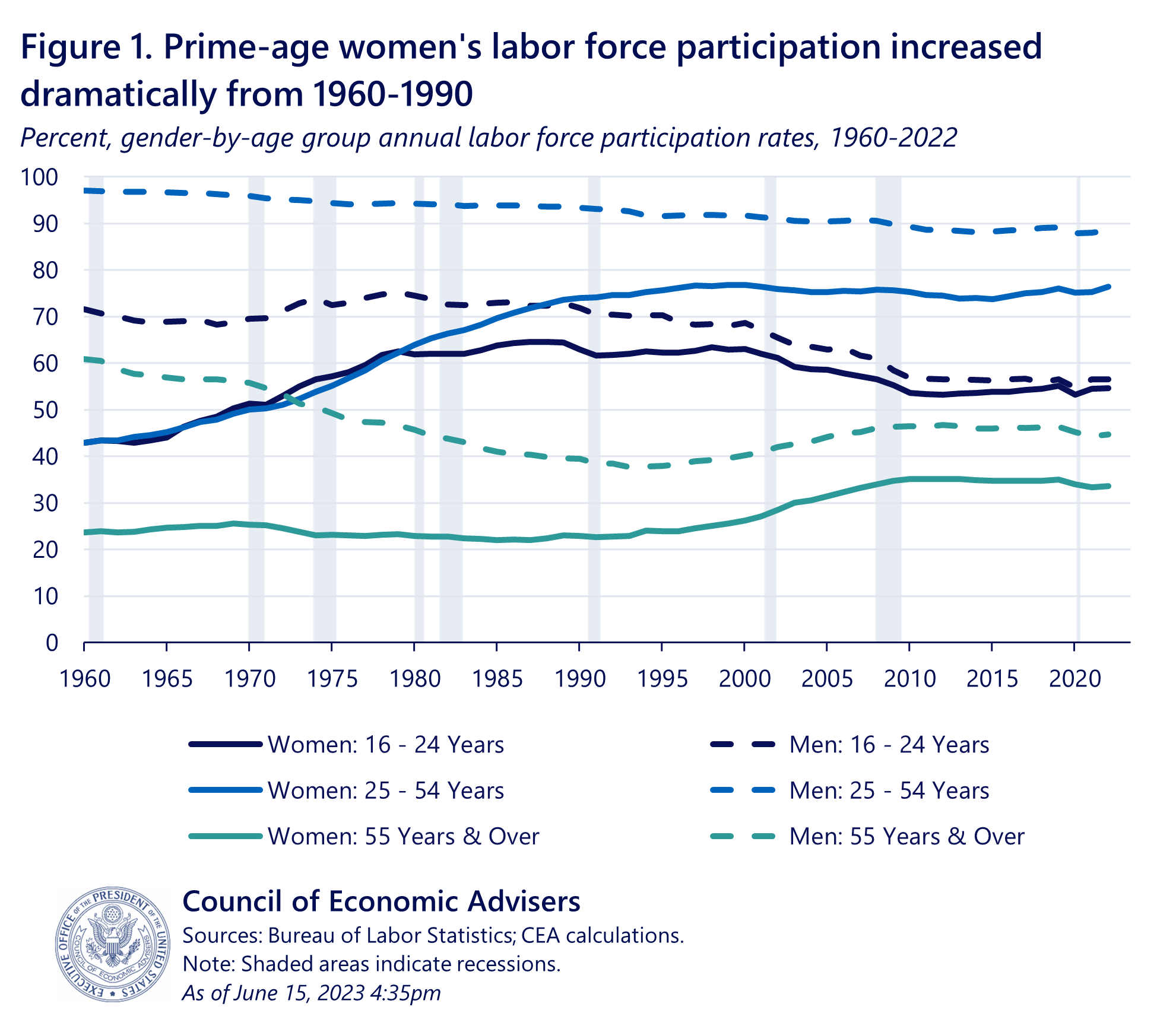

And, challenges remain in ensuring equal pay for equal work. In 2022, among all wage and salary workers usually working full-time, a woman made just 83 cents for every dollar paid to a man. While the gender wage gap shrunk from 23 cents in 2000, it varies by race and ethnicity and is larger for older women. And even though women outpace men in educational attainment at all levels for those ages 25–29, the pay gap among full-time workers exists across all levels of educational attainment (figure 2). Women with postsecondary degrees face a larger penalty than the overall pay gap.

One analysis found that occupational and industry segregation accounted for nearly half of the overall gender pay gap, and that the relative importance of occupation and industry factors in explaining the gap rose considerably over the period of study, 1980–2010. The industries with the largest share of workers who are women may also have the largest pay gaps, highlighting occupational segregation’s importance in persistent inequities. Notably, the gender pay gap does not capture the full picture as women engage in the labor force in different ways and often have to consider their families’ care responsibilities alongside their employment. While measures of the gender pay gap look at full-time, year-round workers, women are more likely than men to be in the labor force part-time and for part of the year. Women are also more likely to be out of the labor force for periods of time, and caregivers’ challenges with managing work and family may lead them to cut back at work by reducing hours or turning down promotions. A recent Urban Institute report quantifies women’s lifetime earnings losses from the career disruptions attached to providing care for children and elders, and they are both substantial and unevenly experienced by women based on their circumstances. When family care costs are measured as a share of lifetime earnings, the caregiving-related earnings losses are particularly large for Hispanic mothers and mothers with lower levels of educational attainment. Thus, the lifetime pay gap is also about the lack of accessible and affordable care infrastructure.

These features of women’s engagement with the workforce came to the forefront during the pandemic. Initially, women’s employment was particularly hard hit. In recent months, however, it has rebounded for prime-age women and now exceeds prepandemic levels. In the initial recovery from the pandemic shock, increases in women’s employment were largely driven by declining unemployment, but in recent months, women entering the labor market has been the larger contributing factor (Figure 3).

What contributed to the strong employment recovery for women? A host of factors are likely responsible for women’s return to the workforce, including school reopenings and greater availability of early childhood, school-age, and long-term care options. In addition, increased remote work options may play a role. During the pandemic, women were more likely to work from home than men, and women are more likely than men to report that telework has made it easier for them to get their work done, meet deadlines, and advance in their job. Recent analysis from the Hamilton Project also suggests that industries that have experienced high job openings relative to hires since 2020 include those that disproportionately employ women, such as health care and social assistance. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a strong labor market is good for workers, and in particular, draws in those who have been historically on the margins of the labor market.

In the 60 years since the passage of the Equal Pay Act, there have been substantial changes in the economy that intersect with women’s engagement. Some changes illuminate signs of progress, while others point to lingering challenges. A continued focus on shared, steady, and stable economic growth, including a policy environment that supports women’s full engagement with the labor force, will not only be better for women and their economic security, but also for their families and communities and our country’s continued economic growth.