Medicaid in Nevada is available to the following legally present residents:

of Federal Poverty Level

Online through HealthCare.gov or through Nevada Health Link. You can also enroll by phone at 800-318-2596.

Eligibility: The aged, blind, and disabled. Also, coverage is available if your household income is up to 138% of poverty (about $16,105 for a single person). For pregnant women, income can be up to 160%, and children are eligible for CHIP with household income up to 200% of poverty.

Nevada expanded Medicaid as of 2014, as called for in the ACA. Nevada’s then-Governor Brian Sandoval was the first Republican governor to commit to expanding Medicaid. Originally, this was an integral part of the ACA, but the Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that expansion was optional, and there are still some states that have not expanded Medicaid as of 2023.

Sandoval cited the fact that the federal government would be paying the vast majority of the costs as a primary motivator for expanding coverage, and noted that although he was generally opposed to the ACA, he believed Medicaid expansion was the correct path.

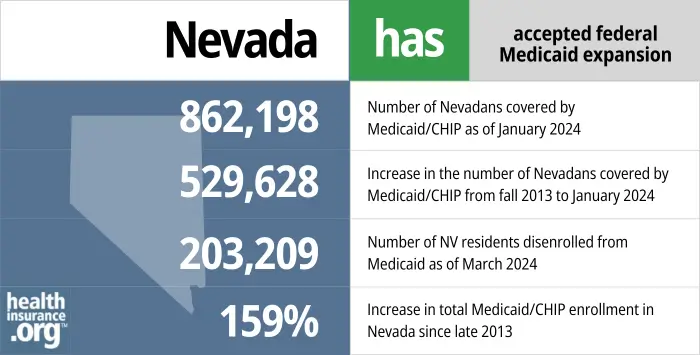

Net enrollment in Medicaid/CHIP in Nevada had grown by more than 528,000 people (a 159% increase) from 2013 through late 2022, to nearly 861,000 people. Across the country, Medicaid/CHIP enrollment was on average 60% higher in 2022 than it was in 2013, due in large part to Medicaid expansion and the COVID-related rules that prohibited states from disenrolling people for three years during the pandemic (more on that in a moment). But Nevada’s 159% increase is an outlier; only Kentucky has had a higher percentage increase in the number of people enrolled in Medicaid since 2013.

We’ve created this guide to help you understand the Nevada health insurance options available to you and your family, and to help you select the coverage that will best fit your needs and budget.

Hoping to improve your smile? Dental insurance may be a smart addition to your health coverage. Our guide explores dental coverage options in Nevada.

Use our guide to learn about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medigap coverage available in Nevada as well as the state’s Medicare supplement (Medigap) regulations.

Short-term health plans provide temporary health insurance for consumers who may find themselves without comprehensive coverage.

Many Medicare beneficiaries receive Medicaid financial assistance that can help them with Medicare premiums, lower prescription drug costs, and pay for expenses not covered by Medicare – such as long-term care.

Our guide to financial assistance for Medicare enrollees in Nevada includes overviews of these programs, including Medicare Savings Programs, Medicaid long-term care benefits, and eligibility guidelines for assistance.

Under the terms of the 2020 Families First Coronavirus Act and the 2022 Consolidated Appropriations Act, states could not disenroll anyone from Medicaid between March 2020 and March 2023 unless the person passed away, moved out of state, or requested disenrollment. So even if an enrollee no longer met the eligibility guidelines, their Medicaid coverage remained in place during the pandemic.

That rule ends March 31, 2023, and states can begin disenrolling ineligible people (and people who don’t respond to renewal packets) as early as April 1, 2023. But Nevada’s first round of disenrollments won’t come until June 1, 2023. The state has opted to begin sending renewal packets on April 1, for enrollees with a May 31 renewal date. Enrollees who no longer meet the eligibility guidelines, and those who fail to respond to the renewal packet, will be disenrolled starting June 1.

The “unwinding” of the COVID-era continuous coverage rule will take 12 months, so some enrollees won’t hear from the state Medicaid office until late 2023 or early 2024. And Nevada has opted to keep each enrollee’s normal renewal date, meaning that if you initially enrolled in January 2021, your renewal date will now be December 31, 2023.

The state will handle as many renewals as possible via the ex parte (automatic) process, meaning that if they have enough information on file to determine that an enrollee is still eligible, they will automatically renew the coverage without the enrollee needing to do anything else. But the rest of the state’s Medicaid enrollees will receive renewal packets roughly eight weeks before their renewal date.

People who are no longer eligible for Medicaid will be able to enroll in a plan offered by an employer (if available) or a plan offered through Nevada Health Link. In either case, the loss of Medicaid will provide a time-limited special enrollment period during which the person will be able to enroll.

With the exception of aged, blind, and disabled enrollees, Nevada Medicaid enrollees living in urban Washoe County and urban Clark County are required to enroll in a Medicaid managed care plan. Roughly three-quarters of Nevada Medicaid enrollees are covered under Medicaid managed care plans.

There are four carriers that provide Medicaid managed care in Nevada:

Nevada has also changed its Medicaid managed care open enrollment period. It used to be in the spring, but it’s now the month of October.

In June 2021, Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak signed S.B.420 into law. This legislation will eventually create a public option program in Nevada, although it won’t be available until 2026.

Under the new program, insurers that submit bids to participate in the state’s Medicaid managed care program will have to also submit bids to offer a public option plan. These plans will resemble the regular qualified health plans that are already for sale in Nevada’s exchange, but they will have to be priced at least 5% lower the first year. Then the prices would have to be lowered in subsequent years, with a target rate reduction of 15% in the first four years. (Washington has already implemented a quasi public option program, and Colorado debuted standardized plans in 2023, with similar targeted rate reductions.)

S.B.420 came four years after Nevada’s legislature made headlines with a public option bill that would have allowed state residents to buy into Medicaid. In June 2017, Nevada’s legislature passed A.B.374 (by a vote of 12-9 in the Senate, and 27-13 in the Assembly). However, Governor Sandoval vetoed it, saying that it left too many questions unanswered.

In his veto message, Sandoval also expressed concern that the people who would have bought into the Medicaid program under A.B.374 might have been the population that’s already privately insured, rather than the uninsured population. Sandoval’s veto left the door open for something similar to A.B.374 in the future; he stated that “the ability for individuals to be able to purchase Medicaid-like plans is something that should be considered in depth.”

A.B.374’s primary sponsor, Democratic Assemblyman Mike Sprinkle, vowed to re-introduce similar legislation during the next session. Nevada has legislative sessions in odd-numbered years only, so the issue was not readdressed in 2018 (although it started to gain traction in other states). Sprinkle proposed Medicaid buy-in legislation early in the 2019 legislative session but resigned soon after and the legislation was never formally introduced.

If A.B.374 had been signed into law, it would have allowed any uninsured Nevada resident to buy into Medicaid, under a program dubbed the Nevada Care Plan. Sarah Kliff has an excellent explanation of how the system would have worked, but in a nutshell, people would have been able to purchase coverage under the Nevada Care Plan via the exchange (Nevada Health Link, which uses HealthCare.gov for enrollment), just like any other health plan sold in the exchange.

ACA premium subsidies would have been used to offset the premiums for Nevada Care Plan. People who don’t qualify for premium subsidies would have had to pay full price for their coverage, but the assumption was that it would have been less expensive than private insurance. The details of the premiums would have been worked out at a later date if the legislation had been implemented, but Medicaid reimburses providers at lower rates than Medicare or private insurance, which makes the coverage less expensive.

The lower reimbursements have also led to fewer providers accepting Medicaid (70.8% of doctors accepted new Medicaid patients, as opposed to 85.3% for Medicare and 90% for privately insured patients). But it’s important to keep in mind that there’s a national trend towards narrow provider network among private plans. So although private plans reimburse providers at higher rates, and doctors are more likely to accept new privately insured patients, members with private insurance are increasingly limited in terms of the scope of the provider network. In other words, even if 100% of providers are willing to accept new privately insured patients, the patients are still limited by the scope of their plan’s provider network, which might be quite restrictive.

As described above, most Nevada Medicaid enrollees are covered by managed care plans (the state contracts with private insurers to cover Medicaid members). The Nevada Care Plan would have also contracted with private insurers.

Former Gov. Sandoval was the first Republican governor to commit to expanding Medicaid, and he was steadfast in his support for Medicaid expansion. Under the Trump administration, legislation to repeal the ACA nearly passed in 2017.

Sandoval was one of five Republican governors — in states that had expanded Medicaid — who pushed to keep Medicaid expansion intact or replace it with something very similar. He sent a letter to House Republicans in January 2017, noting that more than 400,000 Nevada residents had gained coverage as a result of the ACA, in large part because of Medicaid expansion.

Sandoval told lawmakers that while he agreed that states need “more choices, fewer federal mandates and the freedom and flexibility” to implement health care systems that work in each state, he implored House Republicans to “ensure that individuals, families, children, aged, blind, disabled and mentally ill are not suddenly left without the care they need to live healthy, productive lives.”

Nevada’s total Medicaid spending is about $6.4 billion, but the state only pays $1.1 billion of that; the rest is picked up by the federal government. For the population that was already eligible for Medicaid pre-ACA, the state pays a higher percentage of the cost than they do for the newly eligible population. For people who are newly eligible for Medicaid under the ACA, the federal government pays 90% of the cost.

If Medicaid expansion had been repealed and replaced with something that cut federal funding below what the state currently receives, there were concerns that people would have lost coverage or benefits would have been cut. But GOP efforts to repeal or drastically change the ACA were not successful.

From the fall of 2013 through November 2022, total net enrollment in Nevada’s Medicaid program increased by 159% (a significant portion of this growth came early on, with net enrollment growing 90% by early 2017; the COVID pandemic and the moratorium on coverage terminations during the pandemic caused a subsequent enrollment spike between 2020 and 2022).

This is a much higher percentage increase than most states, and is second only to Kentucky where Medicaid enrollment has increased by 165%. The average growth in Medicaid across the U.S. during this period was 60%.

In addition to the newly eligible population, enrollment has been growing among people who were already eligible for Medicaid but had not enrolled prior to the start of the 2014 open enrollment (open enrollment only applies to private plans; Medicaid enrollment is year-round, but the publicity surrounding open enrollment since the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid has encouraged many Medicaid-eligible residents to seek coverage).

Nevada’s uninsured rate fell by 11.2% from 2010 to 2019, with expanded access to Medicaid played a significant role in decreasing the uninsured population. Although there were widespread job and insurance losses attributed to the COVID pandemic, enrollment in Medicaid also spiked sharply upward during the COVID pandemic, emphasizing the importance of the Medicaid safety net when income declines.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.